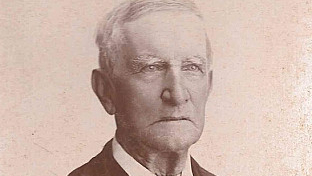

1798-1867

Born in 1798 in Virginia, John Collins emerged as a significant, though reserved, figure in the antebellum South. He arrived in Marengo County, Alabama, in 1837 as an overseer for the prominent Tayloe family, bringing with him a mix of enslaved individuals and free persons of color, including Nellie, his housekeeper and mother to three of his children.

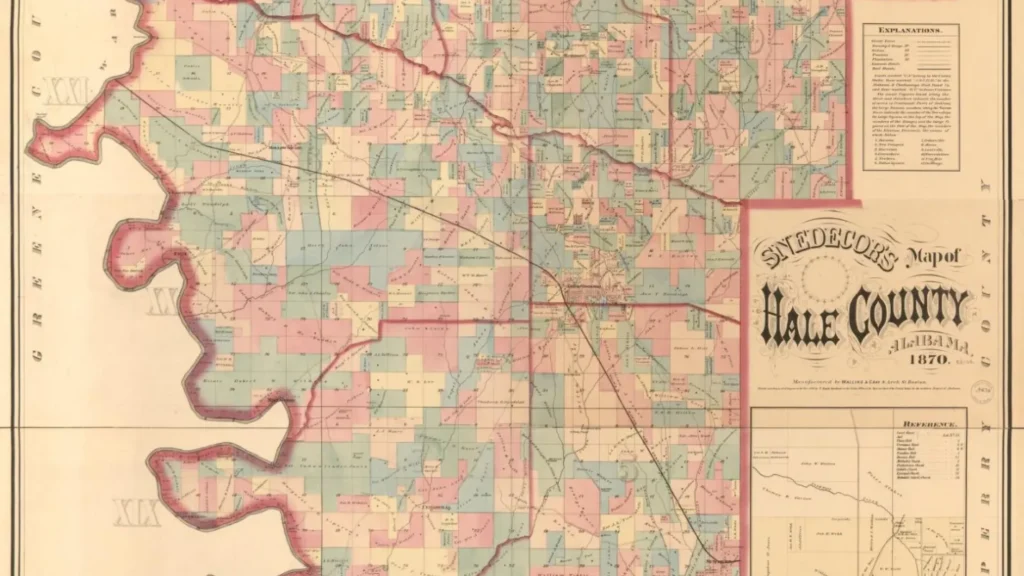

Collins quickly built wealth and landholdings of his own, amassing over 3,000 acres and becoming Marengo County’s largest slaveholder by 1860, with 361 enslaved people. His plantation, “Rodney,” and others he owned, became not only centers of agriculture but also skilled craftsmanship. Many of the enslaved and later freedmen—his own sons included—became blacksmiths, carpenters, and masons, contributing to notable local landmarks like St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church in Prairieville.

Despite never marrying or integrating into the region’s social elite, Collins fathered multiple children by two Black women—Nellie and later Fanny—and made unusual provisions for them in his will. In a remarkable turn for the era, he granted land, homes, trades, and financial support to his formerly enslaved children and their families, laying the foundation for what would become a freedmen’s settlement known as Freetown.

Shortly before his death in 1867, Collins was baptized, and his funeral—attended by both Black and white mourners—marked the end of a life that was as complex as it was quietly influential.

His story reveals not just the contradictions of the Old South, but also a rare legacy of personal responsibility and provision for those once enslaved by him—an uncommon gesture in a deeply divided era.